Nudge - Improving decisions

Book summary on how experts in psychology suggest we should improve our decisions

Back in 2021 I wrote a summary on this book by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein entitled “Nudge.” This is an updated version of the old post, with some revised thinking on the subject.

That subject is, of course, judgment and decision making (JDM) which concerns normative, descriptive, and prescriptive analysis of human judgments and decisions. Nudge theory (“Nudging”) has become a cornerstone of prescriptive JDM. In recent times, it has become rather 'mainstream’ and in this book, the authors offer a way to make better decisions for someone else.

In the book they evaluate choices, biases and the limits of human reasoning from several perspectives. They tell stories about how they trick themselves to becoming victims of the very limitations of thought that they are describing. This is telling, because the very fact that these educated, articulate professionals can trick themselves (even though they know what is happening) demonstrates how tough it is to think clearly. We fall prey to systematic errors of judgment all the time - however, one of the ways of addressing this issue is to improve our ability to identify when this is happening.

Simply put, a nudge is a subtle attempt to influence someone without violating their freedom of choice. Photos of blackened lungs as warnings on cigarette packs, the little messages in the bathroom about how much water is used to wash towels in hotels, and the “open here” symbol on your resealable bag of sweets… are all nudges. Heck, the hourly ‘stand up’ reminder on an Apple Watch is a nudge!

The book defines a nudge as:

“…any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives”

People and Choices

People are making choices all the time; what to eat for breakfast, what to wear, what watch to buy or where to invest money. The key thing to note is that while they may decide without coercion, they do not decide without influence. Depending on the context of the decision, they are almost always influenced noticeably, and often deliberately.

The things that influence people are not always rational, and people are not always aware of what is influencing them. They give an example of black flies painted in the urinals in Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. Men using urinals often don’t aim well and tend to make a mess on the floor around the urinal. However, if you give them a target, even a painted fly, spillage plummets (in this case, by 80%). By contrast, installing cameras in the bathrooms and threatening people with a £500 fine for spillage … would not qualify as a ‘nudge!’

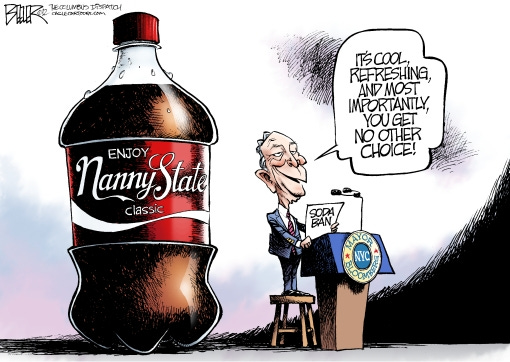

People can be forced to behave a certain way by changing the law, and punishing them for not following it… but quite often, it is more effective to design choices which “nudge” them toward better decisions. In 2012, mayor Michael Bloomberg announced an amendment to New York’s Health Code to would ban any soft drink larger than 16 ounces. This was due to concern for public health, but people were obviously p*ssed off about a “nanny state” which had overstepped its boundaries. Then in 2015, this amendment was repealed as courts ruled the city had exceeded its regulatory authority. Much later, researchers tested out a nudge in McDonald’s restaurants, to determine whether they could nudge people to choose less sugary drinks by simply changing the order in which they appeared on the menu! It worked, and nobody was p*ssed off!

Statistical analyses also suggest that the intervention is capable of producing long-term behavioral change. Comparing the full 12 weeks of pre- and post-intervention sales data, the researchers find an 8% reduction in Coca-Cola consumption and a 30% increase in the selection of Coke Zero.

Of course, people were still free to do as they want, even to act self- destructively and order sugary drinks; he researchers simply increased the odds they would act sensibly (or how they preferred them to act) instead. This approach tries to care for people by guiding them, rather than regulating them. Being nudged can help, because under some circumstances, even when we know better, we don’t always act rationally. (Why else would we be watch collectors?!) As the book says:

We are not for bigger government, just better governance.

Since the book was published, Thaler’s iconic Save More Tomorrow program has helped over 15 million Americans save for retirement, and organ donation rates have increased up to 143% in some jurisdictions (based on how they phrase it as an opt-in versus opt-out choice).

Libertarian paternalism is how the book describes the ideology that underlies nudge theory. Nudging is libertarian in that it preserves the right of the individual to choose a course of action for themselves… while remaining paternalistic in that it aims to influence choices in a way that will make choosers better off. This philosophy has been critiqued for undermining personal freedom. Here’s a link you might find useful too.

Of course, there is an obvious natural moral quandary here, because one could argue we have no right to decide what is better for others and, for example, someone might want to be unhealthy and become obese. Where is the line between subtly helping people make better decisions and outright (sneaky) social engineering? Who has the right to decide what is best for somebody? With the obesity example, governments might seek to use nudges in an effort to help people make healthier food choices which might stymie the obesity problem; but this approach clearly ignores systemic factors which contribute to the problem (poverty, poor nutritional education, unequal access to healthy foods, etc.).

And that’s not to mention field-wide challenges like the replication crisis and media scandals. Problems like publication bias and data falsification aren’t unique to behavioural science – but in a young field, each negative story has a significantly worse impact. Academics are under immense pressure to publish, occasionally leading to unfortunate shortcuts: data falsification, for instance! News media coverage of nudges has long focused on fears of paternalism and manipulation, characterising them as “psychological tricks” and “manipulation” to “increase compliance”. This framing will likely influence whether policy makers and politicians use nudges to complement their own efforts.

Rules of thumb

They move on to explain how people apply “rules of thumb” which bring many biases into play, and many of these have been discussed on SDC before:

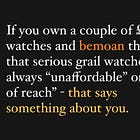

Anchoring - where in which a familiar fact influences your later reasoning. For example, if you first see a shirt that costs £1,000 – then see a second one that costs £100 – you're prone to see the second shirt as cheap. This is a good one to keep in mind for watch buyers; where you see a steel version of a watch for £20,000, and the equivalent in white gold for £25,000 - it starts making the white gold version seem cheap. Of course, this is the reverse interpretation of the rule, but it is still the same principle.

Availability - where you judge risk based on how easily you can obtain related information. So if you’ve been through an earthquake, you’re more likely to buy earthquake insurance, even if you live in a place where earthquakes are highly unlikely. Same for watch insurance - if you've been mugged or robbed, you are more likely to have insurance, even if you have moved to a new place where mugging is unheard of.

Representativeness - where you judge a situation based on how similar it seems to past situations. People who are guided by representativeness see patterns that aren’t there (like gamblers who feel they are on a hot streak). This is quite prevalent in the watch world, especially when it comes to hype-watches. People see how certain models have rocketed, and then assume this will happen again based on certain signs they see in the market - which is of course a fallacy, because the market is highly irrational.

Optimism - human beings tend to be overly optimistic. For instance, 90% of all drivers believe they have above- average skills. People also value gains and losses disproportionately. Once something is yours, you want to keep it. You don’t want to sustain a loss. Many collectors believe their choices to be the best (naturally), but this poisons their opinions o the watches, despite their claims of objectivity.

Status quo bias - this occurs because people like things to stay the same. To help them make productive choices that feel comfortable, do something as simple as setting their current situation as their default option (for example, this is why we often see ads to sign up for something with a low introductory offer, which then auto-renews at a higher price).

Social influences - these have a significant impact. You’re more likely to do something if you see it done often, or if your peers do it. The desire to go along with the social climate is so strong that it can change your perception of reality; you might really see an object differently if your peers insist it looks a certain way. This is obviously the most prevalent and obvious one applicable to watch enthusiasts.

Think about these in the context of watch purchasing for a moment; they all have some sort of relevance, and everyone's got a unique experience where some might apply more than others, so I won't labour the point.

That said, the final section on social influences deserves further attention, as this is one of the key contributors to the existence of ‘hype watches’. While the idea of a hyped watch will never cease to exist, it is helpful for thoughtful collectors (like yourself) to tune in to the signs of a hype train forming, and to figure out whether or not you like the watch. Most importantly, this must be done BEFORE the hype reaches fever pitch - because by the time the hype is real, you will find it extremely difficult to decipher whether you truly like a watch, or are merely buying into the hype.

“Humans are easily nudged by other humans. Why? One reason is that we like to conform.”

Decisions

The authors go on to articulate something basic - which is people need help to make decisions in three categories:

When the stakes are high (insurance)

When the situation is complex or infrequent (buying a property)

When human nature would lead them astray (saving money versus buying watches!).

If the benefit is immediate (chocolate tastes good), but the risks or costs are delayed (you will get fat), getting advice about choices can help. Some think the best choices come from having totally free options in a free market, but that’s not the case. People make bad decisions if they believe bad data, lack key facts or are misled by someone with selfish financial interests. You will remember a lot of these concepts from the previous book summary as well:

For watch buying, or indeed any other decisions, they suggest the “RECAP” (“Record, Evaluate and Compare Alternative Prices”) acronym is a helpful tool to evaluate complex decisions. Frankly, this isn’t rocket science, and I even have a whole post about decision-making too if you care to read it:

Bear in mind having more options is not necessarily a better situation to be in. People have trouble with decisions because the brain has two distinct systems. The first is the “automatic system” (intuitive) which provides immediate emotional responses. Answers come quickly, easily and often intuitively. You use this system when you know something really well, such as when you speak your native language, or when you act out of habit. The second is the “reflective system” (conscious) which requires conscious thought. An example would be the extra effort you might expend to learn and speak a foreign language. You can train your reflective system, but it moves more slowly and, at first, using it seems laborious. This is the exact concept which was discussed in the previous book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow” - they just use different terminology!

Based on this model, people often display irrationality when the automatic system generates biased results and the reflective system is unable to correct it. For example, if you are faced with a large number of options to choose from, you might intuitively decide to stick with the ‘most known’ option, even if that’s not the best option; That is because this saves you from having to evaluate all the available options.

In this case, the issue is that people rely on the automatic system to make a decision that requires the use of the reflective system. Alternatively, in the same situation, people may try to evaluate the options using the reflective system, but fail to do so correctly due to the large amount of information involved. And guess what? This would also cause them to pick an option that isn’t the best one for them.

As an aside, this is probably why Rolex is so successful. Rolex mass-produces close to a million watches a year, but their defect-rate is rather low. Most who own a Rolex will tell you how reliably it serves them, but it does so along with the prestige and aura that comes with the brand.

If you asked a poor kid in Africa what the best watch is - they would say Rolex. Even people who don't care about watches will, at the very least, know of Rolex. When you're thinking of buying an employee a retirement gift, what is the easy choice? Rolex. You may have many watches in your collection, but if you're going away for a one-year expedition involving hiking, heights, water and extreme temperatures... aside from a G-Shock you would probably pick…. a Rolex. It is known for being well made, and reliable.. They do simple things so well, but people tend to take them for granted. This is all to make the point that clearly, Rolex has shifted the luxury watch buying decision into the ‘automatic system’ described above - since, it could be argued, it is unanimous that Rolex is a good choice when you have no time to evaluate options.

An article by Richard Thaler points out how nudges can be used for both good, and bad purposes:

Yet, the same techniques for nudging can be used for less benevolent purposes. Take the enterprise of marketing goods and services. Firms may encourage buyers in order to maximize profits rather than to improve the buyers' welfare (think of financier Bernie Madoff who defrauded thousands of investors).

A common example is when firms offer a rebate to customers who buy a product, but then require them to mail in a form, a copy of the receipt, the SKU bar code on the packaging, and so forth. These companies are only offering the illusion of a rebate to the many people like me who never get around to claiming it. Because of such thick sludge, redemption rates for rebates tend to be low, yet the lure of the rebate still can stimulate sales—call it “buy bait.”

“Nudge, not sludge” - Richard H. Thaler

I bet you already know the most analogous example in the watch world? BUNDLING! The authorised dealer asks you to buy less desirable watches in order to improve your chances of getting a more desirable or rare watch from them. They don't guarantee it, and there is no official policy, but we all know how this works.

What does this mean for me?

It is worth remembering that behavioural economic interventions also have limitations. Nudges can influence positive change in the world – but as Maslow’s famous law of the hammer explains, just because the only tool you have is a hammer…doesn’t make every problem a nail!

Complement, don’t substitute. As two founders of the field explain, “behavioural economics should complement, not substitute for, more substantive economic interventions.” If economic analysts suggest charging more for hyped watches, behavioural economics can determine whether it’s best to lower the price of non-hyped watches, or raise the price of hyped ones.

We can’t always be nudged. Nudges are typically designed to help us pick choices we want. They absolutely will not make us do things we do not want to do, even if they lead to societal good – remember how governments struggled to make people stay at home and isolate during the pandemic?

Temporary fixes for bigger problems. Nudging will never replace serious political or economic issues. For example, nutrition details on fast food will only help consumers pick nutritious options if the nutritious options are financially (or otherwise) accessible to the customer. Nudges can to shift behaviour, but will not change the roots of major problems they aim to solve.

Context matters, be specific. Nudges are rarely universal, and they usually need to be tailored to specific environmental, social, and cultural contexts. For instance, reducing binge-drinking in the U.K. is wildly different than reducing binge-drinking in South Africa. When dealing with different collectors, for example, watch brands can focus on different aspects of relationship building… Japanese might care about honour, while Americans might not! (lol!) As long as context changes, effective nudges will too.

The key takeaway here should be to become more conscious about the presence of a nudge, and the various shapes and forms it may take - more specifically, the nature of both positive and negative nudges. After you've identified it, it is worth questioning the intention of this nudge. Try and consider who benefits from the nudge, but remember that not all things are necessarily malicious, provided there is an alternative explanation for it. At this point you can either accept it, ask the responsible individual or company about it, call out its use, eliminate it, use personal de-biasing techniques to reduce its influence, or take it into account without directly addressing it.

Final thoughts

Using Instagram regularly exposes any watch enthusiast to constant nudges which brands cannot replicate. The level of trust shown between collectors sharing a hobby stands in stark contrast to the mistrust collectors might feel towards a brand which is constantly trying to sell them something.

Brands know this, and this is why content creators with an independent voice often grow their reach to such an extent that causes brands to want to tap into it. The problem here, is the creators then find themselves selling their own independence in order to generate revenue.

The most well-known example is Hodinkee - when Ben Clymer started it, he was a guy who loved watches, and wanted to share his independent unbiased opinion. That independence coupled with the quality journalism and excellent aesthetics, is what led to their growth.

Today, they've come a long way, and are now an authorised dealer for many brands. That's not a bad thing at all, but it does mean that as a consumer, you need to treat what they say differently today - because they no longer exist simply to “serve” the consumer, but to nudge them into buying things which Ben (or Hodinkee) may not necessarily buy themselves, and are certainly not incentivised to criticise openly.

The same is true for individual ‘influencers’ or brand ambassadors… take in all information, but weight it accordingly. See the value of objective opinions, but learn how to discern the objective, from the subjective. Try to always see what an information source has to gain from steering you towards, or away from a particular decision. As a consumer, this is the most valuable thing, so caveat emptor!

🎁 Bonus Link: Some guy wrote a whole doctorate thesis on this subject, which is pretty interesting if you have the time; You can read it here.

If you enjoyed this post, please do me a favour and hit the heart button below; thank you!

People make bad decisions because they are idiots bro

Very interesting read👏🏻

Still unsure if there is such thing as a free choice or if all our choices are “influenced” one way or another…